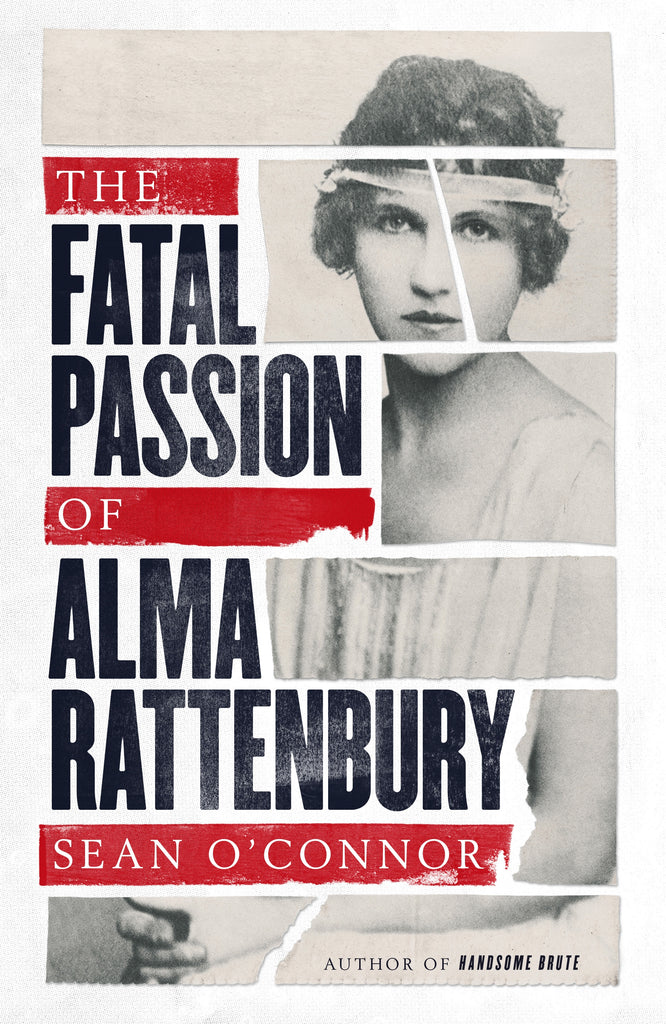

The Fatal Passion of Alma Rattenbury by Sean O’Connor

In 1935, as Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express was flying off the shelves, the British public became gripped by a “real-life shocker”, said Sinclair McKay in The Spectator. Francis Rattenbury, a distinguished architect in his late 60s, was sitting in the living room of his Bournemouth villa when an intruder bashed his skull in with a mallet. It emerged that the culprit was Rattenbury’s 18-year-old chauffeur, George Stoner, who apparently killed his boss in a “spasm of confused jealousy”: for months, he’d been having an affair with the architect’s wife, Alma, 42. To protect her lover, Alma initially claimed responsibility, and “what followed was an extraordinary double murder trial” at the Old Bailey, culminating in Stoner’s conviction and Alma’s acquittal (followed, immediately afterwards, by her suicide). Written in “sensitive and affecting prose”, Sean O’Connor’s account of this “weird and savage killing” is both gripping and powerful.

The case certainly bore all the hallmarks of the “great English murder”, said Thomas Grant in The Times – including a “loveless marriage” and a “suburban mise en scène”. But it also transcended the backdrop of 1930s England, being a “case study in human frailty, jealousy and desire”. No wonder, then, that it so captivated the public, who thrilled to the sensational details: the fact that in an attempt to revive her husband, Alma had jammed his false teeth (which were knocked out by the mallet blow) back into his mouth; or that after committing the murder, Stoner had changed into a pair of silk pyjamas and got into his lover’s bed. While O’Connor isn’t the first writer to chronicle the murder, his account stands out for its meticulous “psychological perspicacity”.

O’Connor’s decision to make Alma the lead character is also wise for she was, in many ways, a “brilliant” woman, said Johanna Thomas-Corr in The Sunday Times. Originally from Canada, she was a precocious violinist who performed to large audiences as a teenager and was subsequently decorated for her work with an ambulance unit in the First World War. Ultimately, O’Connor argues, she became a victim of misogyny, and was tried as much for “immorality” as for “criminality”. Yet for all that the author strives to analyse the wider politics of the case, he can’t get away from the fact that its appeal is “primarily voyeuristic”. What lingers most in the mind is the “harrowing comedy: the false teeth and the crêpe de Chine pyjamas”.